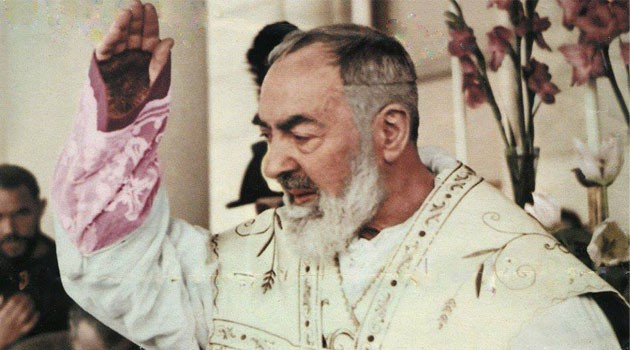

Padre Pio lived a life of prayer and suffering, writes Greg Daly

Padre Pio was a priest with a worldwide following, Pope Paul VI told a gathering of Capuchin Chapter Fathers in 1971, not because he was a philosopher or especially wise or blessed with extensive resources he could use.

“No,” he said, his fame arose “because he said Mass humbly, heard confessions from dawn to dusk and was – it is not easy to say it – one who bore the wounds of our Lord. He was a man of prayer and suffering.”

St Pio of Pietrelcina was born Francesco Forgione in 1887, the second of five children who lived beyond infancy born to Grazio Mario Forgione and Maria Giuseppa di Nunzio, peasant farmers in the small town of Pietrelcina in the Campanian uplands, northeast of Naples.

By the time he was five, he later said, he had decided to dedicate his life to God; certainly he would refuse to play with children of his own age, claiming that they blasphemed. “I have never played in my life,” he later confided sadly, adding that his father had often tried to encourage him to do so. “I was an insipid piece of macaroni, with neither salt nor sauce,” he said.

He helped his parents, working on the land and looking after their small flock of sheep up to the age of 10.

*****

The young Francesco received his first Holy Communion at the age of 11, as was normal then, being confirmed the following year. By this point he had already been drawn to the life of a friar after encountering a Capuchin ‘on the quest’ – seeking donations – and Capuchins at a nearby community in Morcone had said they would be interested in his joining them, but that he would need to be better educated first.

Francesco’s father went to the US in search of work, and sent money home to pay for private tutoring for his son, who attended lessons given by one Domenico Tizzani, a former priest who had left the priesthood so he could marry, and who taught him reading, writing, and a little Latin.

In January 1903, then aged 15, the young Francesco went to Morcone to enter the novitiate of the Friars of the Capuchin Province of Foggia, taking the religious name of Pio some weeks afterwards and making simple profession as a friar a year later.

On his way to begin his studies as a friar, the young Fra Pio took ill, with his appetite dropping, insomnia, and exhaustion, accompanied by fainting spells, vomiting and migraines. His health worsened, and in 1905 his superiors moved him to a community in the mountains in the hope that the change of air would help.

It was to no avail, however, and so doctors advised that he be allowed continue his studies in his home town of Pietrelcina. He made solemn profession in the order there in 1907, and was ordained three years later in the Cathedral of Benevento, though due to his poor health he was, until 1916, allowed to live with his family.

September 1916 saw him being assigned to the seven-strong community of Our Lady of Grace in San Giovanni Rotondo in the Gargano Mountains where he would remain – save during a brief period of military service – until his death in 1968.

The young Padre Pio had first been called up for military service in November 1915, assigned in early December to the 10th Medical Corps in Naples, but within a fortnight he had returned home on medical leave. The following December saw him resuming his assignment, but he was again released on medical leave within a fortnight.

August 1917 marked the beginning of his sole sustained period of military service, with him remaining in barracks until early November, when he again returned to San Giovanni on sick leave. His final period of military service began in early March 1918, but after 10 days he was discharged altogether. He would be plagued by illnesses for the rest of his life.

Some months later, after Mass on the morning of September 20, 1918, Padre Pio knelt alone before the cross in the Church of Our Lady of Grace in the town, withdrawing into himself in a peacefulness he later described as “similar to a sweet sleep”, and prayed fervently.

A month later he wrote to his spiritual director, Padre Benedetto, describing what happened next.

“It all happened in a flash. While all this was taking place, I saw before me a mysterious person, similar to the one I had seen on August 5, differing only because his hands, feet and side were dripping blood,” he wrote, alluding to a vision he had had some weeks earlier.

“The sight of him frightened me: what I felt at that moment is indescribable,” he continued. “I thought I would die, and would have died if the Lord hadn’t intervened and strengthened my heart which was about to burst out of my chest. The person disappeared and I became aware that my hands, feet and side were pierced and were dripping with blood.”

*****

The friar had received the stigmata, wounds corresponding to those Christ suffered on the Cross that were to bring him fame and notoriety over the coming decades, and that would stay with him almost until the very day he died, 50 years later.

This was not the young priest’s first experience of visions, or indeed stigmata. In 1911 he wrote to Padre Benedetto, describing how a red mark had appeared overnight in the centre of his palms, accompanied by acute pain, with a similar pain also afflicting his feet, and in 1915 he told his friend Padre Agostino how he had had visions since his time as a novice, receiving ‘invisible stigmata’ years later.

Although he had sought to share in Christ’s passion in a profound way, Padre Pio had not sought this to be so apparent to others, and wrote in subsequent weeks about his wish that the marks would become invisible to others, as they were reputed to have done for some stigmatics in the past.

“I am dying of pain because of the wound and because of the resulting embarrassment which I feel deep within my soul,” he wrote, expressing the hope that the visible marks be removed. “Will Jesus, who is so good, grant me this grace? Will he at least relieve me of the embarrassment which these outward signs cause me?”

Sufferings

Although he had said he wished his sufferings to be experienced in secret, and although the Capuchin Minister Provincial directed the friary’s Guardian, Fr Paulino of Cascalenda, to “keep quiet and avoid publicity”, it did not take long before reports began to draw attention to Padre Pio and San Giovanni’s small Capuchin community. Rumours spread far and wide of miracles and other wonders linked with the friar in the months following the end of World War One, with the Spanish Flu raging across Italy and Padre Pio and his superior helping administer injections to help people fight the epidemic.

Once word of the phenomenon reached the newspapers, there was no keeping things quiet, and aside from the crowds that descended on the small town in the Gargano Mountains, the attention of scientists and doctors was also aroused.

Sceptical about the whole affair, the Capuchin authorities called on a succession of doctors over the course of 1919 to look into what was happening: first Dr Luigi Romanelli, the head physician of the hospital in Barletta; then Prof. Amici Bignami, head of the University of Rome’s pathology department; then Dr Luigi Festa, who would go on to treat Padre Pio over the years; and finally in July 1920 Dr Romanelli and Dr Festa together.

“In the palm of Padre Pio’s left hand, almost corresponding to the middle of the third metacarpus, I discovered the existence of an anatomical lesion of the tissue, in a more or less circular form, with clean edges, having a diameter of approximately 2cm. This lesion appeared then, as it now appears, to be covered by a reddish brown scab,” wrote Dr Festa.

“During my visit, in order to observe well the lesions of his feet, I helped him, myself, to remove his socks. They were completely drenched with a bloody serum. On the back of both feet, precisely in correspondence to the second metacarpus, I perceived a reddish brown circular lesion, covered by a soft scab which looked exactly like the ones on his hands,” he continued.

“On the anterior region of the left thorax, under the papilla, Padre Pio showed us another lesion in the form of an upside-down cross. It measured about 7cm in length,” he added of the wound in the friar’s side. “None of the surrounding tissues showed any trace of redness or edema. However, there was a more intense and more extensive hypersensitivity to pain in that area than in the normal tissues surrounding the other lesions.”

While the doctors who examined the wounds could not agree on their cause, their reality continued to generate attention, especially as rumours spread of a beautiful fragrance associated with the wounds, of gifts of healing and prophecy and the ability to read the hearts of those who wished to speak with them. Others spoke even of bilocation and levitation.

Reactions to this varied wildly among Church authorities.

Cardinal Pietro Gasparri, the Vatican’s Secretary of State, recommended some people to him and requested Padre Pio’s prayers for the Pope and himself, and Archbishop Edward Kenealy OFM Cap. of Simla in India even came to visit his fellow Capuchin in early 1920, with other leading prelates to come in subsequent months.

The local bishop, Manfredonia’s Archbishop Pasquale Gagliardi, however, suspected fraud, believing the Capuchin community was trying to profit from the affair, and then after Pius XI succeeded Benedict XV a similarly dubious attitude became more prevalent in Rome, with a succession of strictures being placed upon the friar.

The Vatican publicly cast doubt on the possibility that Padre Pio’s wounds had any kind of divine origin, and after briefly meeting the friar on one occasion, without being able to examine the stigmata, the Franciscan founder of Milan’s Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, Agostino Gemelli, declared him “an ignorant and self-mutilating psychopath who exploited people’s credulity”.

In 1933, however, the tide began to turn, with the Pope directing that the ban on Padre Pio’s public celebration of Mass be rescinded, and with the friar being given honorary permission the following year to preach, despite not having a formal license to do so. On acceding to the papacy in 1939, Pope Pius XII encouraged people to visit the Capuchin.

During this period Padre Pio continued to be embarrassed by his condition – in time he would accept it with more confidence – and most photographs show him wearing mittens or coverings on his hands and feet where the bleeding occurred. It was against the background of Italy’s invasion of Albania in 1939 and entry into the Second World War in 1940 that Padre Pio began plans to open a hospital in San Giovanni Rotondo, but the Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza, the ‘Home to relieve suffering’ was not to open until 1956.

*****

In the meantime, the friar’s popularity continued to grow, with 1947 – the year the young Karol Wojtyla, the future Pope St John Paul II, would visit him for Confession – seeing one of the most famous miracles associated with him.

Gemma di Giorgi had been born in the Sicilian town of Ribera on Christmas day, 1939, with eyes that were diagnosed as having no pupils – there was no way light could enter them, and it would be impossible for her to see, with there being no medical cure for the condition.

A relative of her parents who was a nun advised her parents to contact Padre Pio, and was in turn asked by Gemma’s grandmother to write a letter to the friar to tell him of Gemma’s condition.

After sending the letter, the nun had a dream where Padre Pio appeared, asking to see the girl for whom “so many prayers are being offered that they are almost deafening”, with him making the sign of the cross over Gemma’s eyes and promising his prayers after she was presented to him.

The nun received a reply to her letter the following day and urged Gemma’s parents to take their daughter to visit the friar.

Gemma and her grandmother set out, and on the way Gemma told her mother she could see the sea and a ship.

When they reached San Giovanni, they were met by Padre Pio who promptly greeted Gemma, and heard her confession, touching her eyes with his wounded hand and drawing the sign of the cross upon her. Years later she described how she had opened her eyes then, seen the bearded priest, and began to cry.

Upset that Gemma had not asked for healing, Gemma’s grandmother asked the friar to hear her confession, and pleaded for Gemma to be helped see.

“Do you have faith, my daughter? The child must not weep and neither must you for the child sees, and you know she sees,” he replied, alluding to how she had spoken of seeing a ship on the sea on the way there.

Still without pupils, the Italian government considers Gemma legally blind to this day, though she walks about unaided. “I see with the eyes of God, not the eyes of my body” she told people in the Philippines in 2003, declaring: “God has put Padre Pio like a radiant light for our century.”

In 1956, a year in which the friar was left bedridden with exudative pleuritis for four months, the hospital he had planned since 1956 opened, with the help of a grant of $325,000 from the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA).

The following year Pius XII granted Padre Pio dispensation from his vow of poverty so that he might directly supervise the hospital project, but the friar’s detractors used this as another weapon with which to attack him, charging him with misappropriation of funds and spreading rumours that led to a new wave of Vatican investigations and renewed restraints on his ministry and even on his relations with other friars.

The accession of Blessed Paul VI to the papacy in 1963 changed everything, however. All accusations were dismissed and Padre Pio was free at last to celebrate his ministry fully and openly in his final years, drawing vast crowds to San Giovanni Rotondo and inspiring people throughout the world.

In 1999, 31 years after the friar’s death, he was beatified, and in 2002 Pope St John Paul II canonised him as a saint of the Church.

Greg Daly

Greg Daly